Year after year, the ocean’s most successful killer is not the great white shark. It’s not the deadly jellyfish. Not even monster waves or hurricane-force winds. Your worst ocean nightmare during a day at the beach is more likely to be a rip current, experts say.

Every year beachgoers drown in these strong rushes of water that pull swimmers away from the shore. Nearly half of all rescues made by lifeguards at ocean beaches are related to rip currents,

How they work:

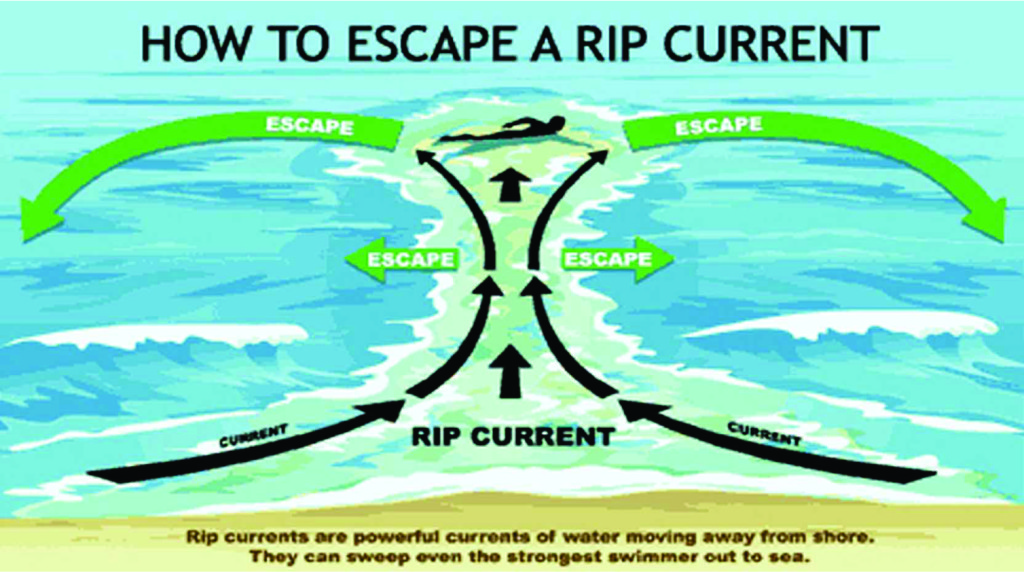

A common perception is that rip currents pull you underwater, but in reality they’re strong, narrow currents that flow away from the beach.

“Essentially they’re rivers of the sea,” said Wendy Carey, a coastal hazards specialist

“People start going under because they panic, and they feel like the current is pulling them under,” Carey said. “There is no current that will pull you under in the ocean.”

There are many different types of rip currents, and they form in several ways. Quickly changing wave heights can trigger a rip current, such as from large sets of swells. Rip currents can also occur at sandbar breaks, where water is funneled out to sea. These channels in sand bars lie just off the beach. When water returns to the ocean, it follows the path of least resistance, which is typically through these channels. And strong rip currents often appear next to structures such as piers, jetties and groins, Carey said.

The key ingredient in all rip currents is breaking waves. “If there are no breaking waves, there won’t be any rip currents,” Carey said.

The risk of rip currents is determined by many factors, including weather, tides, local variations in beach shape and how waves break offshore. Some beaches may have rip currents nearly all the time, while other beaches almost never see the dangerous flows.

These strong and often very localized currents are capable of carrying unsuspecting swimmers out to sea. The currents usually move at 1 to 2 feet per second (0.3 to 0.6 meters per second) but stronger ones can pull at faster than 6 feet per second (1.6 m per second). That’s the same pace as a world record Olympic freestyler, Carey said. “Even an Olympic swimmer would find themselves going backward in a rip current pulse,” she said.

Rip currents can speed up dramatically in a short time. The unsteady flow of a rip current is similar to standing in a river on land. The strong flow can sweep you off your feet, Carey said. “An adult standing in waist deep water in a rip current would find it hard to stay in the same place,” she said.

Rip tide a misnomer

Heavy breaking waves can trigger a sudden rip current, but rip currents are most hazardous around low tide, when water is already pulling away from the beach. In the past, rip currents were sometimes called rip tides, which was a mistake, Carey said. “Tides are really slow changes in water level and by themselves do not induce a rip current,” she said. “A rip current is not at all a tide.”

Scientists have been studying rip currents for more than 100 years. In the past decade, advances in measurement techniques have provided many new insights into how these complicated currents work. Researchers now toss GPS-equipped drifters into the surf to precisely track rip current movements and speed. Acoustic Doppler current profiling (similar to sonar) has revealed the inner workings of rip currents. Highly detailed laser measurements of the beach environment shows how water and topography combine to trigger rips.

“There is a new understanding of rip current flow and behavior,” Carey said.

What to do

Surviving a rip current starts before you even enter the water, Carey said. “Avoidance is the most important thing. Swim at a lifeguard-protected beach and talk to the lifeguard on duty about ocean conditions for the day,” she said. “It’s also really important to know how to swim and how to float before you venture ankle-deep into the ocean.”

Learning how to spot a rip current can help you avoid getting caught, Carey added. For instance, rip currents above deep sandbar channels look like calm patches of water. These calmer waters are often between turbulent breaking waves, presenting an inviting pathway to inexperienced beachgoers. “Sometimes people inadvertently enter the water in one of the most dangerous spots just because it looks calm,” Carey said.

It is easy to be caught in a rip current. Most often it happens in waist deep water, experts say. A person will dive under a wave, but when they resurface they find they are much further from the beach and still being pulled away.

What they do next can decide their fate.

Those who understand the dynamics of rip currents advise remaining calm. Conserve energy. A rip current is like a giant water treadmill that you can’t turn off, so it does no good to try and swim against it.

“Even small rips can flow faster than a person can swim. You should not try to swim against the rip,” Carey said.

Rip currents are often narrow, and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the United States Lifesaving Association (USLA) suggest trying to swim parallel to the shore and out of the current. Once you’ve gotten out of the current, you can begin swimming back to shore.

“You may want to swim toward whitewater, where the waves are breaking,” Carey said. “That may help guide you out of the rip.”

However, if it is too difficult to swim sideways out of the current, try floating or treading water and let nature do its thing. You’ll wash out of the current at some point and can then make your way back to shore. The latest research indicates that many rip currents circulate back to shore, and would carry stranded swimmers along with the current, but not all rip currents rotate in this manner, Carey said.

“There are still occasions where the drifters would not be brought back,” she said.

If swimming doesn’t seem to be working for you, conserve your energy by floating or treading water and try to get the attention of someone on shore, hopefully a lifeguard.

And if you’re with someone who is caught in a rip current, don’t attempt a rescue. Call 911, get help from a lifeguard and throw a floatation device into the rip current. “There are many tragic stories where someone went into a rip current to try and save someone else and they became drowning victims themselves,” Carey said.

Additional reporting by Becky Oskin, Live Science Senior Writer